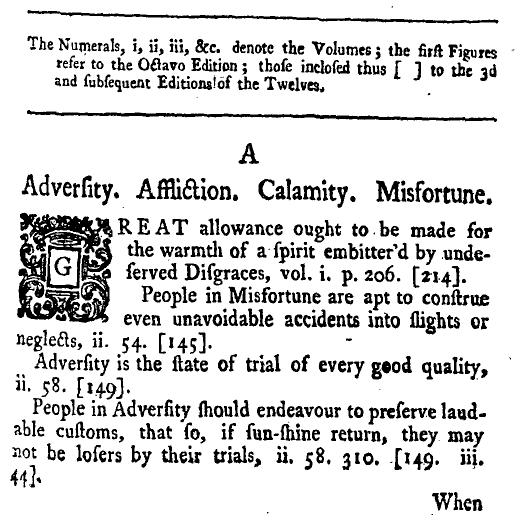

It’s hard enough to read Samuel Richardson’s Pamela. It’s even harder to finish his later, longer epistolary novel: Clarissa, or, the History of a Young Lady (1748) [984,870 words]. Having toiled through both books, I was resting easy until confronted with a curious volume that I volunteered to present on in a graduate seminar on the 18C novel. The title? A collection of the moral and instructive sentiments, maxims, cautions, and reflexions, contained in the histories of Pamela, Clarissa, and Sir Charles Grandison (1755). The CMIS, as I’ll abbreviate it, consists of several hundred topics, each with multiple entries that consists of a short summary and a page reference. Here’s an example from the Clarissa section, thanks to ECCO.

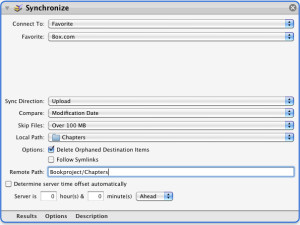

Without going into the meaning or importance of these references, I want to focus on a practical problem: how could we extract every single citation of the eight-volume “Octavo Edition” of 1751? Our most basic data structure should be able to capture the volume and page numbers and associate them with the correct topic. While Richardson may very well have used some kind of card index, I can safely say that no subsequent reader or critic has bothered to count anything in the CMIS. But its very structure demands a database!

Without going into the meaning or importance of these references, I want to focus on a practical problem: how could we extract every single citation of the eight-volume “Octavo Edition” of 1751? Our most basic data structure should be able to capture the volume and page numbers and associate them with the correct topic. While Richardson may very well have used some kind of card index, I can safely say that no subsequent reader or critic has bothered to count anything in the CMIS. But its very structure demands a database!

As a novice user of Python, it will be somewhat embarrassing to share the script I wrote to “scrape” the page numbers from an e-text of the CMIS (subscription required) helpfully prepared by the wonderful people and machines at the Text Creation Partnership (TCP). The TCP’s version was essential since the OCR-produced text (using ABBYY FineReader 8.0) at the Internet Archive is riddled with errors.

I started by cutting and pasting two things into text files in my Python directory: (1) the full contents of the Clarissa section of the CMIS and (2) a list of all 136 topics (from “Adversity. Affliction. Calamity. Misfortune.” to “Youth”) pulled from the TCP table of contents page.

import sys import re from collections import defaultdict from rome import Roman

The first step is to import the modules we’ll need. “Sys” and “re” (regular expressions) are standard; default dictionary is a super helpful way to set the default key-value to 0 (or anything you choose) and avoid key errors; rome is a third-party package that converted Roman numerals to Arabic.

# Read in two files: (1) digitized 'Sentiments' (2) TOC of topics

f1 = open(sys.argv[1], 'r')

f2 = open(sys.argv[2], 'r')

# Create topics list, filtering out alphabetical headings

topics = [line.strip() for line in f2 if len(line) > 3]

# Dictionary for converting volumes into one series of pages

volume = {1:348, 2:355, 3:352, 4:385, 5:358, 6:431, 7:442, 8:399}

startPage = {1:0, 2:348, 3:703, 4:1055, 5:1440, 6:1798, 7:2229, 8:2671}

This section of code reads in the two files as ‘f1’ and ‘f2.’ I’ll grab the contents of f2 and write them to a list called ‘topics,’ doing a little cleanup on the way. Essentially, the list comprehension filters out the alphabetical headings like “A.” or “Z.” (since these are less than three characters in length. Now I have an array of all 136 topics which I can loop over to check if a line in my main file is a topic heading. You probably noticed that the references in CMIS were formatted by volume and page. I’d like to get rid of the volume number and convert all citations to a ‘global’ page number. The first dictionary lists the volume and its total number of pages; the second contains the overall page number at which any given volume begins. Thus, the final volume starts at page 2,671.

counter = 0

match = ''

# Core dictionaries: (1) citations ranked by frequency and (2) sorted by location

frequency = defaultdict(lambda: 0)

location = {}

# Loop over datafile

for line in f1:

if line.strip() in topics:

match = line.strip()

counter += 1

location[match] = [counter, []]

OK, the hardest thing for me was making sure the extracted references got tossed in the right topic bin. So I initialized a counter that would increment each time the code hits a new topic. The blank string ‘match’ will keep track of the topic name. The loop goes through each line in the main file, f1. The first if statement checks if the line (with white space stripped off) is present in the topics list. If it does, then counter and match update and a key with the topic name (e.g. “Youth.”) is created in the location dictionary. The values for this key will be a list: location[“Youth.”][0] equals 136, since this is the last topic.

elif re.search(r'[iv]+..*(?=[)', line):

citation = re.search(r'[iv]+..*(?=[)', line)

process = [x for x in re.split('W', citation.group()) if re.match('(d|[iv]+)', x)]

current = ''

for i in range(len(process)):

if re.match(r'[iv]+', process[i]):

current = process[i]

else:

#frequency[(int(Roman(current)), process[i])] += 1

page = startPage[int(Roman(current))] + int(process[i])

frequency[page] += 1

location[match][1].append(page)

This is the heart of the code. The else-if statement deals with all lines that are NOT topic headings AND contain the regular expression I have specified. Let’s break down the regex:

'[iv]+..*(?=[)'

Brackets mean disjunction: so either ‘i’ OR ‘v’ is what we’re looking for. The Kleene plus (‘+’) says we need to have at least one of the immediately previous pattern, i.e. the ‘[iv]’. Then we escape the period using a backslash, because we only need to get the Roman numerals up to eight (‘viii’) followed by a period. The second period is a special wildcard and the Kleene star right after means we can have as many wildcards as we want up until the parentheses, which contain a lookahead assertion. The lookahead checks for a left bracket (remember how the citations always include the duodecimo references in brackets). In English, then, the regex checks for some combination of i’s and v’s followed by a period that is followed, at some point, by a bracket.

The process variable runs through the string returned in the regex expression and splits the Roman and Arabic numerals by whitespace, appending them to a list. The string “People in Adversity should endeavour to preserve laud|able customs, that so, if sun-shine return, they may not be losers by their trials, ii. 58. 310. [149. iii. 44].” would be returned as “ii. 58. 310. [” by the regex and then turned into [ii, 58, 310] by process. Current is an empty string designed to hold the current Roman numeral so we know, for instance, which volume to match up page 310 with. In the final lines, the current Roman numeral is converted to its startPage number and the page number is added to it. Then the frequency dictionary for that specific page is incremented and the key for the current topic in the location dictionary is updated with the newly extracted page number.

Obviously, this is a rather crude method. It’d be fun to optimize it (and I do need to fix it up so that it can deal with the handful of citations marked by ‘ibid.’), but scraping is supposed to be quick-and-dirty because it really only works with the specific document or webpage that you’re encountering. I doubt this code would do anything useful for other concordance-like texts in the TCP. But I would love to hear suggestions for how it could be better.

In a later post, I’ll talk about the problems I’ve faced in visualizing the data extracted from the CMIS.