The Chronicle published a lengthy review article last week on the science of brain mapping. The article focuses on Ken Hayworth, a researcher at Harvard who specializes in the study of neural networks (called connectomes). Hayworth believes, among other things, that we will one day be able to upload and replicate an individual human consciousness on a computer. It sounds like a great film plot. Certainly, it speaks to our ever-evolving obsession with our own mortality. Whatever the value of Hayworth’s prediction, many of us are already storing our consciousness on our computers. We take notes, download source material, write drafts, save bookmarks, edit content, post blogs and tweets and status updates. No doubt the amount of our intellectual life that unfolds in front of a screen varies greatly from person to person. But there are probably not too many modern writers like David McCullough, who spends most of his time clacking away on an antique typewriter in his backyard shed.

Although I still wade through stacks of papers and books and handwritten notes, the vast majority of my academic work lives on my computer, and that can be a scary prospect. I have heard horror stories of researchers who lose years of diligent work in the blink of an eye. I use Carbon Copy Cloner to mirror all of my data to an external hard drive next to my desk. Others might prefer Time Machine (for Macs) or Backup and Restore (for Windows). But what if I lose both my computer and my backup? Enter the wide world of cloud storage. Although it may be some time before we can backup our entire neural net on the cloud, it is now fairly easy to mirror the complicated webs of source material, notes, and drafts that live on our computers. Services like Dropbox, Google Drive, SpiderOak, and SugarSync offer between 2 and 5 GB of free space and various options for syncing local files to the cloud and across multiple computers and mobile devices. Most include the ability to share and collaborate on documents, which can be useful in classroom and research environments.

Although I still wade through stacks of papers and books and handwritten notes, the vast majority of my academic work lives on my computer, and that can be a scary prospect. I have heard horror stories of researchers who lose years of diligent work in the blink of an eye. I use Carbon Copy Cloner to mirror all of my data to an external hard drive next to my desk. Others might prefer Time Machine (for Macs) or Backup and Restore (for Windows). But what if I lose both my computer and my backup? Enter the wide world of cloud storage. Although it may be some time before we can backup our entire neural net on the cloud, it is now fairly easy to mirror the complicated webs of source material, notes, and drafts that live on our computers. Services like Dropbox, Google Drive, SpiderOak, and SugarSync offer between 2 and 5 GB of free space and various options for syncing local files to the cloud and across multiple computers and mobile devices. Most include the ability to share and collaborate on documents, which can be useful in classroom and research environments.

These free services work great for everyday purposes, but longer research projects require more space and organizational sophistication. The collection of over 10,000 manuscript letters at the heart of my dissertation, which I spent three years digitizing, organizing, categorizing, and annotating, consume about 30 GB. Not to mention the reams of digital photos, pdfs, and tiffs spread across dozens of project folders. It is not uncommon these days to pop into a library or an archive and snap several gigs of photos in a few hours. Whether this kind of speed-research is a boon or a curse is subject to debate. In any event, although they impose certain limits, ADrive, MediaFire, and Box (under a special promotion) offer 50 GB of free space in the cloud. Symform offers up to 200 GB if you contribute to their peer-to-peer network, but their interface is not ideal and when I gave the program a test drive it ate up almost 90% of my bandwidth. If you are willing to pay an ongoing monthly fee, there are countless options, including JustCloud‘s unlimited backup. I decided to take advantage of the Box deal to backup my various research projects, and since the process was far from straightforward, I thought I would share my solution with the world (or add it to the universal hive mind).

Below are the steps I used to hack together a free, cloud-synced backup of my research. Although this process is designed to sync academic work, it could be modified to mirror other material or even your entire operating system (more or less). While these instructions are aimed at Mac users, the general principles should remain the same across platforms. I can make no promises regarding the security or longevity of material stored in the cloud. Although most services tout 256 bit SSL encryption, vulnerabilities are inevitable and the ephemeral nature of the online market makes it difficult to predict how long you will have access to your files. The proprietary structure of the cloud and government policing efforts are critical issues that deserve more attention. Finally, I want to reiterate that this process is for those looking to backup a fairly large amount of material. For backups under 5 GB, it is far easier to use one of the free synching services mentioned above.

Step 1: Signup for Box (or another service that offers more than a few GB of cloud storage). I took advantage of a limited-time promotion for Android users and scored 50 GB of free space.

Step 2: Make sure you can WebDAV into your account. From the Mac Finder, click Go –> Connect to Sever (or hit command-k). Enter “https://www.box.com/dav” as the server address. When prompted, enter the e-mail address and password that you chose when you setup your Box account. Your root directory should mount on the desktop as a network drive. Not all services offer WebDAV access, so your mileage may vary.

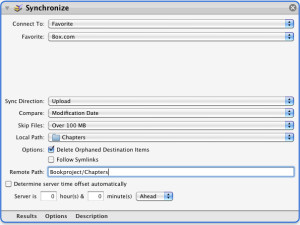

Step 3: Install Transmit (or a similar client that allows synced uploads). The full version costs $34, which may be worth it if you decide you want to continue using this method. Create a favorite for your account and make sure it works. The protocol should be WebDAV HTTPS (port 443), the server should be www.box.com, and the remote path should be /dav. Since Box imposes a 100 MB limit for a single file, I also created a rule that excludes all files larger than 100 MB. Click Transmit –> Preferences –> Rules to establish what files to skip. Since only a few of my research documents exceeded 100 MB, I was fine depositing these with another free cloud server. I realize not everyone will be comfortable with this.

Step 4: Launch Automator and compile a script to run an upload through Transmit. Select “iCal Alarm” as your template and find the Transmit actions. Select the action named “Synchronize” and drag it to the right. You should now be able to enter your upload parameters. Select the favorite you created in Step 3 and add any rules that are necessary. Select “delete orphaned destination items” to ensure an accurate mirror of your local file structure, but make sure the Local Path and the Remote Path point to the same place. Otherwise, the script will overwrite the remote folder to match the local folder and create a mess. I also recommend disabling the option to “determine server time offset automatically.”

Step 4: Launch Automator and compile a script to run an upload through Transmit. Select “iCal Alarm” as your template and find the Transmit actions. Select the action named “Synchronize” and drag it to the right. You should now be able to enter your upload parameters. Select the favorite you created in Step 3 and add any rules that are necessary. Select “delete orphaned destination items” to ensure an accurate mirror of your local file structure, but make sure the Local Path and the Remote Path point to the same place. Otherwise, the script will overwrite the remote folder to match the local folder and create a mess. I also recommend disabling the option to “determine server time offset automatically.”

Step 5: Save your alarm. This will generate a new event in iCal, in your Automator calendar (if you don’t have a calendar for automated tasks, the system should create one for you). Double-click the event to modify the timing. Set repeat to “every day” and adjust the alarm time to something innocuous, like 4am. Click “Done” and you should be all set.

Automator will launch Transmit every day at your appointed time and run a synchronization on the folder containing your research. The first time it runs, it should replicate the entire structure and contents of your folder. On subsequent occasions, it should only update those files that have been modified since the last sync. There is a lot that can go wrong with this particular workflow, and I did not include every contingency here, so please feel free to chime in if you think I’ve left out something important.

If, like me, you are a Unix nerd at heart, you can write a shell script to replicate most of this using something like cadaver or mount_webdav, rsync, and cron. I might post some more technical instructions later, but I thought I should start out with basic point-and-click. If you have any comments or suggestions – other cloud servers, different process, different outcomes – please feel free to share them.

UPDATE: Konrad Lawson over at ProfHacker has posted a succinct guide to scripting rsync on Mac OS X. It’s probably better than anything I could come up with, so if you’re looking for a more robust solution and you’re not afraid of the command line, you should check it out.

Cross-posted at HASTAC