I will always have a soft spot for The Simpsons. Although I no longer watch the show on a regular basis, it was an important part of my childhood, and I paid homage to it in one of my first academic journal articles. During its heyday in the mid-90s (when I had to sneak around my parents’ prohibition in order to watch it), the show developed a reputation for unusually intelligent, iconoclastic humor. It offered smart, politically-conscious satire, served up by smart, politically-conscious writers. The Simpsons seems to employ more Harvard graduates than McKinsey & Company – the writer’s room is essentially a jobs program for the Harvard Lampoon. Naturally, therefore, its central villain, the inimitable C. Montgomery Burns, is a Yale man (class of 1914). With his absurd anachronisms and ruthless, mustache-twirling embodiment of corporate capitalism, Burns is easily one my favorite characters. So when I heard that the show put out an episode about his return to campus, I could not resist.

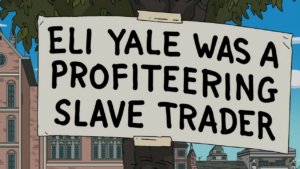

To my surprise, the episode makes direct reference to an essay I published two years ago, establishing that Elihu Yale was a slave trader. The piece, which I wrote in a few hours in response to a conference, probably receives more attention than all of my more traditional scholarship combined. During the debate over the renaming of Calhoun College, it appeared on reddit and the Wall Street Journal, made its way onto Wikipedia, and was tweeted out by historian colleagues and celebrities such as Ann Coulter (which, I will admit, made me throw up a little in my mouth). In the episode, it forms part of a larger joke about liberalism gone mad at Yale. On a tour of campus, Burns encounters teachers who were fired for celebrating Columbus Day, students who call him “worse than Hitler,” and signs that read: “Shakespeare is murder” and “Eli Yale was a profiteering slave trader.” Aghast, Burns wonders aloud if Yale is “still a coven of capitalism, where evil money can acquire a patina of virtue” – and he gets in a good crack about “ruthless media disruptor Samuel F. B. Morse.”

When Burns attempts to endow a Department of Nuclear Plant Management, he is thwarted by students, who are described as “highly-entitled wusses.” Instead, school administrators point out that they “need to hire more deans to decide which Halloween costumes are appropriate.” The latter refers to an actual incident sparked by a memo about racist/offensive Halloween costumes, which made national news. Although the episode does not mention the recent rebirth of Calhoun College as Hopper College, the subtext is clear. This is neither the time nor the place to rehash those debates. (You can read my thoughts on Grace Hopper here.) But the implication that students seeking redress for social injustice are “wusses” left me feeling deeply uneasy.

Students on campuses across the country face unprecedented economic pressures, shameful levels of sexual assault, and administrators eager to capitalize on “diversity” while doing very little to support underprivileged students. These same students have every right to demand a space free from racism or discrimination, and those of us on faculty and staff have a moral obligation to stand with them. By ridiculing and dismissing student protestors, the writers of The Simpsons are doing exactly the opposite. Instead of using their position of tremendous privilege and authority to question the status quo, they use it to attack a vulnerable population. Instead of speaking truth to power, as in some of the show’s greatest episodes, they seek to undermine the relatively powerless.

Of course, no group or idea should be exempt from parody. The ability to laugh at oneself demonstrates humility, strength, and self-awareness. And to be fair, the episode attempts a muddled critique of Trump University and the for-profit education industry. Yet the whole tone of the campus visit feels hackneyed and mean-spirited rather than fresh or funny. The writers’ clear desire to be the next William F. Buckley results in a ham-fisted diatribe that stands at odds with the show’s subversive tradition. (PCU did a better job with similar material over twenty years ago. David Spade’s tirade at the film’s end about “whiny crybaby minorities” shows that not much has changed.)

I understand the argument of some pundits who think that student protests about costumes and memorials are misguided or absurd. With the Trump administration rolling back protections for disadvantaged groups and the environment at a blistering pace, fussing over the names of buildings seems like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. But justice comes in all forms, and our colleges and universities should embody the change that we want to see in the world. As historian Craig Wilder argued recently: “Campuses are not museums for the emotional and psychological bigotries of the alumni.” Reckoning with that truth is an important victory and will set the stage for other victories in the future. That Elihu Yale or Mr. Burns would no longer feel at home on a college campus is a good thing. Although it can be a long and arduous process, successful student movements prove that evil money can indeed become virtuous.