The following is the text of a presentation I gave at the Antislavery Usable Past workshop at the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation. For more information about the conference and the paper, please click here.

I would like to talk about two things today: capitalism and abolitionist missionaries in Africa in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. I am interested in both of these things, and I think they are related in an important way. First, I want to dwell for a bit on capitalism as an interpretive lens for understanding the problem of slavery and abolition. And that leads me to this quote:

Whoever is not willing to talk about capitalism should also keep silent about fascism.

– Max Horkheimer (1939)

This is a famous quote. We can call it the Horkheimer thesis. It’s quite controversial, but it’s also very true, and most of the controversy is about the extent of its true-ness. There also seems to be a nineteenth century parallel to the Horkheimer thesis. There is no direct quote, but it might be paraphrased as follows:

Whoever is not willing to talk about capitalism should also keep silent about slavery.

-Edward Baptist

Sven Beckert

Seth Rockman

Caitlin Rosenthal

Walter Johnson

Dale Tomich

etc., etc.

We might call this the new synthesis in slavery studies, which has emerged rather quickly over the past two or three years (although it’s rooted in earlier work and much older debates in the field).

While earlier work tended to focus on individual slaveholding economies and the extent to which they were capitalist, or pre-capitalist, or feudal (or whatever Eugene Genovese thought slavery was about), this new work sidesteps those questions by exploring how African chattel slavery was integral to the entire process of capitalist globalization. Although they did not have all of the benefit of hindsight, contemporaries recognized this curious phenomenon as it was unfolding, and this brings me to the following quote from Marx:

Direct slavery is as much the pivot upon which our present-day industrialism turns as are machinery, credit, etc. Without slavery there would be no cotton, without cotton there would be no modern industry. It is slavery which has given value to the colonies, it is the colonies which have created world trade, and world trade is the necessary condition for large-scale machine industry…Slavery is therefore an economic category of paramount importance.

-Karl Marx (1846)

This is a great quote to use with students in classroom discussions, or as an essay prompt (Do you agree with Marx? Why or why not?). In a way, Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton is an extremely elaborate answer to this question. The new synthesis on nineteenth-century chattel slavery also helps to explain, at least in part, why slavery continues to persist in the modern global economy. If slavery is integral to capitalism, at least in some sense, and if we are living in an age of unprecedented capitalist hegemony, as pretty much everyone seems to agree, then of course slavery will continue to be a problem. And it will continue to be a problem, I would like to suggest, until we fully acknowledge and understand the central role that various forms of unfree labor play in capitalist economies. And this brings me to the topic of abolitionism.

If, as the new synthesis suggests, one cannot talk about slavery without talking about capitalism, then the same must be true, at least to some extent, about abolitionism. If slavery is integral to capitalism, then antislavery must, at least in some way, be about anti-capitalism. Now, I don’t want to suggest that abolitionists were running around in Che Guevara t-shirts, waving AK-47s, and talking about the dictatorship of the proletariat (although a minority of abolitionists, I think, did stuff that could be considered roughly equivalent). Many, if not most, abolitionists sought a limited form of capitalism, without excess greed, or excess wealth, or excess exploitation. In that sense, their views were very similar to those recently articulated by Pope Francis, and they can be traced, in part, to the same egalitarian traditions in the New Testament (in its Catholic form, it’s known as Distributism).

As most of you folks probably know, there is an extensive literature on the relationship between capitalism and abolitionism, stretching back to Eric Williams, who set the terms of the debate, for better or for worse, back in the 1940s. But it’s been relatively quiet over the past few decades, and it remains to be seen how the new synthesis in slavery studies will challenge what we know about abolitionism. Even if the answers are not clear at this point, however, it should not stop us from asking the questions.

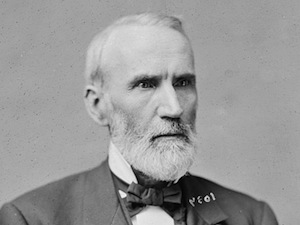

In thinking about the lessons of antislavery (the question of this conference), it occurred to me to investigate what the original abolitionists had to say about this. What lessons did they see in their movement? As it turns out, they said quite a bit, and some of them even said stuff about capitalism. One of the most important moments, when abolitionists gathered to collectively reflect on their movement, was the big “Antislavery Reunion” in Chicago in the summer of 1874. And one of the featured speakers at this reunion was George Julian. A congressman from Indiana, Julian was an old-school abolitionist, a lawyer who had helped organize both the Free Soil and the Republican parties. His long involvement in the movement had led him to some of the same conclusions that Marx had reached earlier, and he also anticipated some of the conclusions of the new synthesis in slavery studies.

In thinking about the lessons of antislavery (the question of this conference), it occurred to me to investigate what the original abolitionists had to say about this. What lessons did they see in their movement? As it turns out, they said quite a bit, and some of them even said stuff about capitalism. One of the most important moments, when abolitionists gathered to collectively reflect on their movement, was the big “Antislavery Reunion” in Chicago in the summer of 1874. And one of the featured speakers at this reunion was George Julian. A congressman from Indiana, Julian was an old-school abolitionist, a lawyer who had helped organize both the Free Soil and the Republican parties. His long involvement in the movement had led him to some of the same conclusions that Marx had reached earlier, and he also anticipated some of the conclusions of the new synthesis in slavery studies.

Julian’s speech in Chicago was aptly titled: “The Lessons of the Anti-Slavery Conflict.” And in this speech he devoted a large amount of time to what he called “the slavery question in other forms.” One of the most important lessons of antislavery, Julian argued, was women’s rights. This will come as no surprise to students of first-wave feminism and its deep roots in abolitionist political culture. But equally, if not more important, according to Julian, was the struggle against capitalism. “African slavery was simply one form of the domination of capital over the poor,” he argued.

The system of Southern slavery was the natural outgrowth of that generally accepted political philosophy which makes the protection of property the chief end of Government. It was only the strongly-emphasized expression of the maxim that ‘capital should own labor’…The labor question, as I have often said, is the natural successor and logical sequence of the slavery question. It is the slavery question, renewed in other forms and generalized. The abolition of poverty is the next work in order after converting the African chattel into a man, and the Abolitionist who does not see this fails to grasp the logic of the Anti-Slavery movement.

-George Julian (1874)

Not long after Julian gave his speech about capital and the persistence of different forms of enslavement, the abolitionist conventioneers gathered to celebrate the American Missionary Association. “It alone of all the earlier Anti-Slavery organizations retains a vigorous existence,” read their report. “It embodies much of the old Abolition feeling,” they continued, “now happily turned toward the intellectual and moral culture of the freedmen.” So, in other words, here was another antislavery lesson.

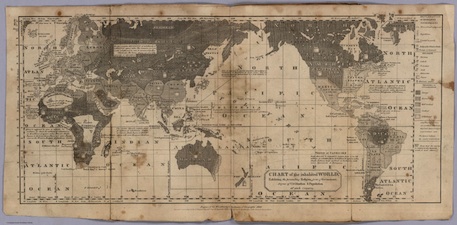

Founded in 1846, but with roots reaching back a decade earlier, the AMA was the largest, the longest-running, and the most wide-reaching abolitionist organization in the United States. Although best known for its educational work among former slaves, the AMA supported similar efforts among Chinese immigrants, Native Americans, and the white working class. And its foreign department included stations in Canada, Egypt, Haiti, Hawaii, Jamaica, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Thailand, and the Marquesas Islands, among other places.

The AMA’s Mendi Mission, located in what is now southern Sierra Leone, was its flagship project for almost four decades, running between 1842 and 1882. Established as an extension of the Amistad slave revolt, the mission was a transatlantic branch of the Underground Railroad and a key frontier of action and imagination in the global contest over slavery. The mission also challenges conventional interpretations of the Civil War era. Well over one hundred ministers and teachers of different genders, colors, and backgrounds served as a bridge linking religion and politics across two continents, and their attempts to reconstruct Africa prefigured and complimented postwar southern reconstruction. There is a lot more that needs to be said about the AMA and the Mendi Mission, but in the time that I have remaining, I will limit myself to some of the missionaries’ experiments in free labor and labor discipline, because this is where I think the African-American story of the Mendi Mission intersects with the big, macro-level, global capitalism story that I mentioned at the beginning of my talk.

I should point out that by “free labor,” abolitionists meant free as in speech, not free as in beer. (Although I think there are some interesting tensions in that language.) There is a modest body of literature on the free produce and free labor movements, but surprisingly little on the movements’ African dimensions. As it turns out, agricultural production was a longstanding project at the Mendi Mission. As early as 1839, mission founder Augustus Hanson had suggested farm work as a path to racial uplift. Abolitionist missionary William Raymond concurred. “The slave trade will not be stopped,” he prophesied, “and the people raised from their degradation, until their attention is directed to the cultivation of the soil.” By the 1850s, the mission’s geographic headquarters at Kaw Mendi boasted a small field, which supplied root vegetables and other staples for local consumption. The African men who worked on the farm were intended as living advertisements for the free labor system, and the missionaries kept meticulous records of their attendance, productivity, and wages. Although the mission was never self-sustaining, manual labor of this sort was considered important. Working on the land would encourage discipline and “manly independence.” By occupying idle hands and minds, it would prevent the cycle of civil war that fed the slave trade. Most importantly, it would provide an economic alternative to mercantile networks in tobacco, rum, weapons, and slaves.

The Mendi missionaries made several attempts to introduce an export economy in free labor cotton and sugar. Although cotton grew naturally in the region and Mende weavers carried on an extensive clothing trade, the missionaries’ goal was to increase output on a global scale. Henry Miles, a leader in the Free Labor movement in the United States, encouraged these efforts. It was, he wrote to his African colleagues, “useless to attempt to put down slavery by argument or even by legislation while we persist in upholding the slaveholder by acting the part of agents in commerce for his benefit.” After his son, Richard, signed up for the Mendi Mission, Miles sent cottonseeds and facilitated contact with free labor manufacturers in Manchester, England.

With the start of the Civil War in 1861, the missionaries saw a golden opportunity to enter the global marketplace. Since “American Slavery owes its continued existence and power to the great and increasing demand for cotton,” they reasoned, a new supply from African workers would put the entire system out of business. Although retired from the mission by this time, abolitionist celebrity George Thompson proposed a 500-acre cotton plantation on the West African littoral, complete with its own city, over which he would “have just as full control, as any king.”

So that gives you a sense of some of the stakes involved in this project, and the big plans that American abolitionists had in store for the African economy. And it’s worth pointing out that it was not only the Mendi Missionaries doing this. The missionaries maintained active links with the African Civilization Society, the British Freedmen’s Aid Society, Liberian settlers, the Basel mission on the Gold Coast, and other groups attempting similar free labor experiments. Pro-slavery apologists even floated fanciful ideas in the 1850s and 1860s to send southern American slaveholders and overseers to Africa to teach labor discipline to the allegedly “lazy” inhabitants. To these men, the entire continent was “only a great wilderness of loungers.” Abolitionists sometimes fell into similar rhetoric, but unlike their opponents, they placed the blame for African “degradation” on the slave trade and its legacies within the global economy.

Perhaps the most visible symbol of the Mendi Mission was the John Brown steamship. Named after the militant abolitionist, who had led an ill-fated raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, the ship was a symbol of the bustling economic transition that the missionaries hoped to accomplish in Africa. In fact, it was the first mercantile vessel of its kind in that part of the continent. As a representative of the mission, it refused to transport spirituous liquors or other material considered harmful to African industry and progress. Constructed in the early 1880s, as the memory of John Brown began to be supplanted in the United States by the defeat of Reconstruction and the culture of reconciliation, the John Brown steamship also sent a message that the memory of radical abolitionism would live on, outside the borders of the United States.

Of course, all of these utopian schemes for the economic transformation of Africa were no match for reality. Most free labor projects failed miserably due to a lack of funds, poor organization, or tropical disease. Where it took hold, an increase in legitimate commercial activity actually tended to bolster indigenous forms of slavery. At the same time, the Mendi missionaries faced strikes, desertions, theft, and a general lack of interest in their strict labor regime. Although the missionaries eventually established a moderately successful lumber mill at Avery station, near what is now Mano on the Bagru River, the settlement was never self-supporting, and the mill was eventually destroyed during the anti-colonial “Hut Tax” Revolt of 1898.

It would be easy to conclude that the Mendi missionaries did not learn the lessons of Marx, or George Julian, or the new synthesis in slavery studies. But that is not really true. Most of the missionaries were at least vaguely aware of these issues. And most missionaries realized that economic transformation alone would not be enough to completely abolish slavery. All of the missionaries recognized the central role of warfare in the perpetuation of African slavery (and slavery more generally). In fact, we can still see this today, in places like Iraq and Syria. “Put an end to war,” wrote missionary James Tefft in 1854, “and the slave-trade cannot be carried on. Stop the slave-trade, and there remains no cause for war.” Of course, exactly how to go about stopping war, or exactly how to go about stopping the slave trade, were complicated strategic questions.

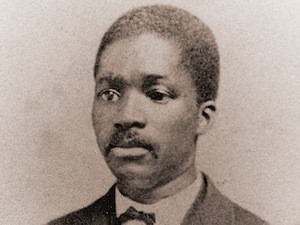

There was an interesting split among the Mendi missionaries on this issue. Some of them, perhaps the majority, felt that British, or American, or French imperial forces were necessary allies of the mission. Providing the secular stick to the mission’s cultural carrot, these forces would pacify the African landscape and create a more business-friendly environment for foreign investment and trade. Others felt that such efforts were counter-productive, merely replacing one form of warfare with another. And they tended to support the rights of indigenous African communities to determine their own fate. Missionary Barnabas Root, who was educated by American abolitionists in Africa, and who led a church in Reconstruction-era Alabama before returning to his home, made this point clear. Rather than forcing foreign cultural norms on West African people, he wrote in 1876: “I am strongly in favor of going half way to meet the people in these respects when it can be done…I would prefer that Christianity come unattended by that officious hand-maiden modern civilization.”

There was an interesting split among the Mendi missionaries on this issue. Some of them, perhaps the majority, felt that British, or American, or French imperial forces were necessary allies of the mission. Providing the secular stick to the mission’s cultural carrot, these forces would pacify the African landscape and create a more business-friendly environment for foreign investment and trade. Others felt that such efforts were counter-productive, merely replacing one form of warfare with another. And they tended to support the rights of indigenous African communities to determine their own fate. Missionary Barnabas Root, who was educated by American abolitionists in Africa, and who led a church in Reconstruction-era Alabama before returning to his home, made this point clear. Rather than forcing foreign cultural norms on West African people, he wrote in 1876: “I am strongly in favor of going half way to meet the people in these respects when it can be done…I would prefer that Christianity come unattended by that officious hand-maiden modern civilization.”

So what can the experience of abolitionist missionaries in Africa in the nineteenth century teach us about eliminating slavery in the twenty-first century? It is difficult to summarize such an extremely complex and important history in a short talk. But, even with this very cursory overview, I think we can discern two broad lessons. First, if we want to fight slavery effectively, we need to develop a more robust critique of global capitalism. Campaigns such as Slavery Footprint, which are a positive development, are not sufficient. No movement for free labor or fair trade, by itself, has ever succeeded in abolishing slavery. If we remain silent about capitalism, then we cannot talk about abolitionism. Secondly, if slavery is rooted in, and feeds off of warfare, then anyone interested in the abolition of slavery should be working alongside groups seeking an end to war – especially the culture of war that favors quick solutions by throwing guns and missiles at a problem, rather than long-term structural change. Without a more sophisticated appreciation of the intimate relationship between capitalism and slavery, and without participating in larger coalitions with groups working for a culture of peace, the movement against modern-day slavery will not succeed.