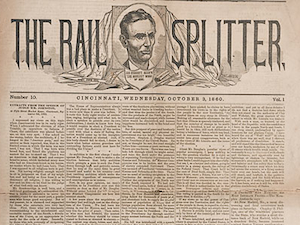

Walter Isaacson is enamored of great men. As an author, he has published popular biographies of Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, Henry Kissinger, and Steve Jobs (the latter sold 379,000 copies in its first week alone). As President of the elite Aspen Institute, he arranges for great and powerful men to network with other great and powerful men. As the managing editor of Time magazine and the CEO of CNN, he has reached for the heights of great man-dom himself. One of his books is simply called The Wise Men. He even edited a collection on what he calls “the Elusive Quality of Greatness.” This makes his latest study all the more surprising. Called The Innovators, it is anchored by a demure Victorian woman who was largely ignored during her short life and, for about 150 years thereafter, considered not really that great. A kind of group portrait of the digital revolution, the book begins and ends with Ada Lovelace.

The daughter of Lord Byron, socially privileged, chronically ill, and problematically married, Lovelace was the quintessential Victorian aristocrat. She was also a mathematical prodigy who envisioned the first computer program in a breathtaking work of theorizing tucked away at the bottom of an English translation of an Italian article about the work of someone else. When I screened a documentary about the Countess of Lovelace in my Digital History course this year, not a single student knew her name. By the end of the class period, all of them agreed that she was one of the most significant figures in the history of computing. (One of my students cited her as inspiration to write her senior thesis on the digital gender divide and recent efforts to bridge it.)

Isaacson is hardly the first to notice Ada Lovelace. That she occupies such a prominent place in his narrative is due to years of work by generations of scholars who have written articles and news stories, produced films and biographies, and founded an international Ada Lovelace Day. Isaacson does not shy away from her influence, and he connects her story to that of Grace Hopper, the Yale-educated mathematician who became one of the first and most important software developers. Like Lovelace, from whom she took inspiration, Hopper was overshadowed by her male collaborators. But she is slowly attracting more attention and now has her own annual conference. Together, these two privileged white women stand athwart the group of privileged white males who occupy the majority of Isaacson’s book.

The attention paid to Lovelace and Hopper is laudable. Still, they seem like simply another addition to the laundry list of great men. As Roy Rosenzweig pointed out long ago, the history of the digital age is just as much about the military-industrial complex and the Cold War and economic globalization as it is about eccentric geniuses toiling in obscurity. Focusing on the great men (or great women or great queer folk) can render invisible all of the not-so-great labor that birthed and midwifed the digital revolution. Much of this work was done by women. Women literally were the first computers. So this begs the question: what would a feminist history of computing look like?

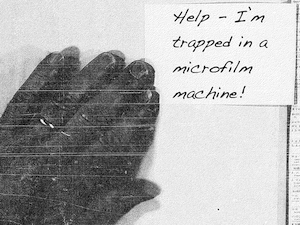

To me, it looks like a severed hand. All of us who use Google Books on a regular basis have seen them at some point, floating, disembodied, anonymous, usually feminine or non-white. People have been blogging about the hands for years. A Google worker famously lost his job after trying to film the bodies attached to them. The hands are printed in art books and compiled on Tumblr. Many of them evoke themes of race and class. Or, as the New Yorker put it, “a brown hand resting on a page of a beautiful old book.” The perceived disparity between the brown and the beautiful speaks volumes. Sometimes the hands communicate subtle messages. Consider the bejeweled hand pointing to a chapter in a biography of Napoleon. Or get lost in the psychedelic mystery that is A Serious Call to the Christian World, authored by “Jews.” One of my personal favorites is a small appendage with long nails and neon purple finger-condoms grasping the title page of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. Who says there is no poetry in the everyday? In an instant, “the invisible hand” of the market is laid bare. These glitches are the material traces of the workers who actually power the digital revolution. The severed hand is the embodiment of a history.

To me, it looks like a severed hand. All of us who use Google Books on a regular basis have seen them at some point, floating, disembodied, anonymous, usually feminine or non-white. People have been blogging about the hands for years. A Google worker famously lost his job after trying to film the bodies attached to them. The hands are printed in art books and compiled on Tumblr. Many of them evoke themes of race and class. Or, as the New Yorker put it, “a brown hand resting on a page of a beautiful old book.” The perceived disparity between the brown and the beautiful speaks volumes. Sometimes the hands communicate subtle messages. Consider the bejeweled hand pointing to a chapter in a biography of Napoleon. Or get lost in the psychedelic mystery that is A Serious Call to the Christian World, authored by “Jews.” One of my personal favorites is a small appendage with long nails and neon purple finger-condoms grasping the title page of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. Who says there is no poetry in the everyday? In an instant, “the invisible hand” of the market is laid bare. These glitches are the material traces of the workers who actually power the digital revolution. The severed hand is the embodiment of a history.

Rooting through some early microfilm, I came across more hands. Black-and-white, grainy, but unmistakably female, complete with wedding rings and painted nails. Looking at another microfilm reel from the early 1940s, I saw yet more hands, also ringed, also female, and I realized that this had been going on for a long time. Like the women who programmed the first computers, their work was both invisible and glaring, ordinary and extraordinary. The same technology that was attempting to erase this manual labor was making it ever more visible. Here was an army of Ada Lovelaces, working in secret, processing material, cataloging, inventing, filming, scanning, and providing the essential groundwork and infrastructure for all that showy greatness. Although perhaps not of the Isaacsonian ilk, they quietly demand our attention.

Cross-posted at HASTAC