Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and the internet and airwaves are awash in an orgy of commentaries and memorials. What can a digital humanist add to this conversation? Well, for starters, one could ask what the assassination of President Kennedy would look like in the age of social networks, smart phones, and instantaneous communication (bigbopper69: JFK shot in dallas OMG!!! 2 soon 2 no who #grassyknoll). NPR’s Today in 1963 project, which is tweeting out the events of the assassination as they occurred, day-by-day, hour-by-hour, may actually provide a good sense of what it was like to be there in real time. For those of us born decades after the fact, the deluge of digitized photos, videos, documents, and other artifacts enables a kind of full historical immersion that is not quite the same as time travel but close enough to be educationally useful.

Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and the internet and airwaves are awash in an orgy of commentaries and memorials. What can a digital humanist add to this conversation? Well, for starters, one could ask what the assassination of President Kennedy would look like in the age of social networks, smart phones, and instantaneous communication (bigbopper69: JFK shot in dallas OMG!!! 2 soon 2 no who #grassyknoll). NPR’s Today in 1963 project, which is tweeting out the events of the assassination as they occurred, day-by-day, hour-by-hour, may actually provide a good sense of what it was like to be there in real time. For those of us born decades after the fact, the deluge of digitized photos, videos, documents, and other artifacts enables a kind of full historical immersion that is not quite the same as time travel but close enough to be educationally useful.

One of the more interesting statistics to come out of this year’s commemoration is that “a clear majority of Americans (61%) still believe others besides Lee Harvey Oswald were involved” in a conspiracy to kill President Kennedy. Indeed, historical data show that a majority of Americans have suspected a conspiracy since 1963, at times reaching as high as 81 percent of respondents. This raises all sorts of interesting questions for our current moment, when rumor and misinformation spread as easily as the truth and technophiles celebrate the wisdom of the crowd while solemnly proclaiming the death of the expert. Especially after the recent revelations of unprecedented government spying, including secret courts and secret backdoors built into consumer software, Americans seem to have little reason to trust authority. So what is the role of popular knowledge in the age of digital history?

It would be easy to dismiss the various JFK assassination theories as just another example of what Richard Hofstadter called “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Yet to do so would ignore the important function of rumor, gossip, conspiracy theories, and other forms of popular wisdom as material forces in the shaping of our world. Getting at the truth behind major events is, of course, the prime directive of all good history, digital or otherwise. A certain degree of analytical distance, strict rules of evidence, and overt argumentation are what separate professional historiography from simple nostalgia. But what counts as truth can sometimes be just as revealing as the truth itself. The alleged assassination of President Zachary Taylor is a case in point.

When Taylor, the twelfth president, died suddenly of an unidentified gastrointestinal illness just sixteen months into his first term in office, rumors spread that he had been eliminated by political rivals. Taylor’s death, in July 1850, came at a time of heightened tension between supporters and opponents of slavery. Although a slaveholder himself and the hero of an expansionist war against Mexico, Taylor took a moderate position on the slavery question and appeared to oppose its extension into the western territories. His actions may have troubled some of the more ardent southern politicians, including Senator – and future Confederate President – Jefferson Davis. Not long after his predecessor’s tragic demise, newly-minted President Millard Fillmore signed the Compromise of 1850, which had stalled under Taylor’s administration. The legislation included territorial divisions and an aggressive fugitive slave law that helped to set the stage for the looming Civil War.

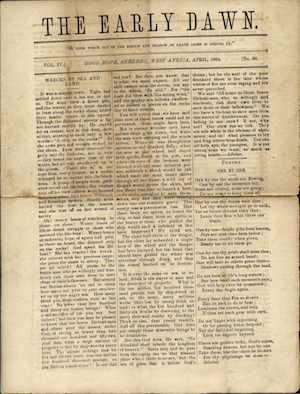

I will not rehash the specific circumstances of Taylor’s illness, which is conventionally ascribed to a tainted batch of cherries and milk. Suffice it to say that the rapid and inexplicable nature of his death, which fit the profile for acute arsenic poisoning, coupled with the laughably inept state of professional medicine, left plenty of room for speculation. Members of the rising antislavery coalition, soon to be called the Republican Party, were suspicious that the President had met with foul play. Nor were their suspicions limited to Taylor. Over time, the list of alleged assassination victims grew to include Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, and James Buchanan, among others.

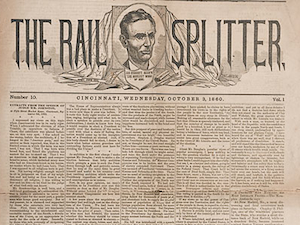

Republicans worried that Abraham Lincoln would meet a similar fate after the contentious presidential election of 1860. Even before the election, letters poured in warning the candidate about attempts to poison his food and begging him to keep a close eye on his personal staff. I counted at least fourteen warning notes in a very cursory search of the Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Many of them mention President Taylor by name. “Taylor was a vigorous man, of good habits and accustomed to active life and trying duties,” wrote a supporter from Ohio, “and that he should fall a solitary victim to cholera, in a time of health, after eating a little ice cream is quite unsatisfactory.” After carefully studying the circumstances of Taylor’s death, another concluded that “the Borgias were about.” Yet another consulted a clairvoyant who warned of an active conspiracy to poison the President. In a speech responding to Lincoln’s assassination five years later, railroad magnate and women’s rights advocate George Francis Train mentioned in passing that slaveholders had “poisoned Zachary Taylor,” as if it were a matter of fact.

John Armor Bingham, one of the three lawyers tasked with prosecuting the Lincoln assassination conspiracy and the primary author of the fourteenth amendment to the Constitution, reportedly spent some time investigating Taylor’s death. His research, presumably conducted during or shortly after the Lincoln trial in 1865, led him to believe that Taylor had been poisoned and that Jefferson Davis had helped to precipitate the plot. It is a striking claim, if true. Davis was Taylor’s son-in-law by an earlier marriage, and the two were known to be friends. Indeed Taylor uttered his final words to Davis, who stood vigil at his deathbed. Bingham also suspected that Davis was involved in Lincoln’s death, which is unlikely, though not impossible, since there is evidence to suggest that Lincoln’s assassin had contact with Confederate spies in the period leading up to the attack. Whatever the case, Davis was decidedly ambivalent about the effect of the President’s removal on the flagging war effort in the South.

Although historians have shown sporadic interest in Bingham – he was an early antislavery politician and U.S. Ambassador to Japan in addition to his important legal and constitutional roles – I could find no substantial information about his investigation into a conspiracy to murder Zachary Taylor. The finding aids for Bingham’s manuscripts at the Ohio Historical Society and the Library of Congress did not reveal anything related to Taylor. A superficial perusal of similar material at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, which holds some of Bingham’s records pertaining to the Lincoln Assassination, also failed to turn up anything significant. Still, my search was limited to document titles and finding aids and did not dig very deep into the actual content of his papers. Perhaps some enterprising digital historian could investigate further?

Uncertainty about Taylor’s death continued to smolder until the early 1990s, when an assiduous biographer managed to secure permission to exhume his body and run scientific tests on the remains. Early results showed no evidence of arsenic poisoning, though later research concluded that those results were unreliable. According to presidential assassination experts Nancy Marion and Willard Oliver, there is no definitive proof either way, and thus the ultimate cause of Taylor’s death remains a mystery. While I think the evidence for natural causes is persuasive, the assorted circumstantial and physical evidence for poisoning is certainly intriguing. More intriguing still is the fact that so many contemporaries, including major political figures, were convinced that Taylor had been intentionally targeted.

The confusion surrounding Taylor’s death speaks to the awesome influence of the “Slave Power Conspiracy” that gripped the nation for much of the nineteenth century. Aspects of this conspiracy theory could be extreme, but as the historian Leonard Richards has shown in great detail, the Slave Power was a quantitative reality that could be measured in votes, laws, institutions, and individuals. Although historians can debate the extent to which it was a self-conscious or internally unified collusion, thanks to the three-fifths clause, the spread of the cotton gin, and other peculiarities of antebellum development, there really was a Slave Power in early American politics. Bingham may have been overzealous when it came to the sinister machinations of Jefferson Davis, but there is no question that Davis and his ilk shared a broadly similar agenda. Popular knowledge about the death of Zachary Taylor, whatever its veracity, reflected a real concern about the grip of a small group of wealthy aristocrats over the social, economic, and political life of the country, just as theories about the death of JFK reflect a real concern about the exponential growth of the U.S. national security state.

A few days ago, Americans celebrated the 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address, another epochal moment in their national history. Unlike the sadness and uncertainly surrounding the JFK assassination, this was a moment of optimism and unity, typified by the filmmaker Ken Burns, who solicited readings of the Address from everyone from Uma Thurman to Bill O’Reilly, including all five extant U.S. Presidents. Lost in patriotic reverie, it is easy to lose sight of the bitter, divisive, and bloody conflict that formed the broader context for that document. It is no accident, perhaps, that the recently unmasked espionage programs developed by the United States and Great Britain were named after civil war battles – Manassas and Bullrun for the NSA, Edgehill for the GCHQ. The choice of names appears to be intentional. Both battles were pivotal moments, the first major engagements in a long and destructive war that would result in the birth of a modern nation. Likewise, these surveillance systems appear to be the first step in a prolonged global war for digital intelligence. Is this evidence of a conspiracy? Or is it yet more evidence of the extent to which conspiratorial thinking has infiltrated modern political culture – just another example of the new paranoid style?