Those who have been following my career over the past few years (hi Mom) know that I have been working on a major new digital project called Princeton & Slavery. This was an exciting time to engage with questions of slavery and higher education, with new initiatives launched at Columbia, Georgetown, Harvard, Rutgers, and elsewhere. Princeton & Slavery is the largest study of its kind yet produced, featuring hundreds of primary sources and around 90 original essays. Altogether, the site totals over 400,000 words – the equivalent of about 1,600 printed pages. The sheer size of the project was necessary because of the extent to which traditional archives and narratives seek to elide or minimize the significance of black lives and the impact of slavery on our past and present. At its core, the website is a counter-archive that presents a different, more complicated story.

My work on the project also coincided with a wave of campus protests. Starting with events in Ferguson and the University of Missouri, students around the country organized marches, walk-outs, sit-ins, and teach-ins. Inspired and led by women of color, participants made concrete demands for racial justice, equity, and inclusion. At Princeton, a courageous group of students occupied the president’s office for two days. This was the broader context in which the project took shape, and my participation in these movements and dialogues with student activists were essential to my work on the site. In fact, student protestors spurred the creation of a university “Histories Fund” that allowed us to expand the scope of the project.

Below is the substance of my talk at the recent Princeton & Slavery symposium, which featured a keynote address by Toni Morrison and commentary by a number of leading historians. In the talk, I discuss some of our findings about student demographics.

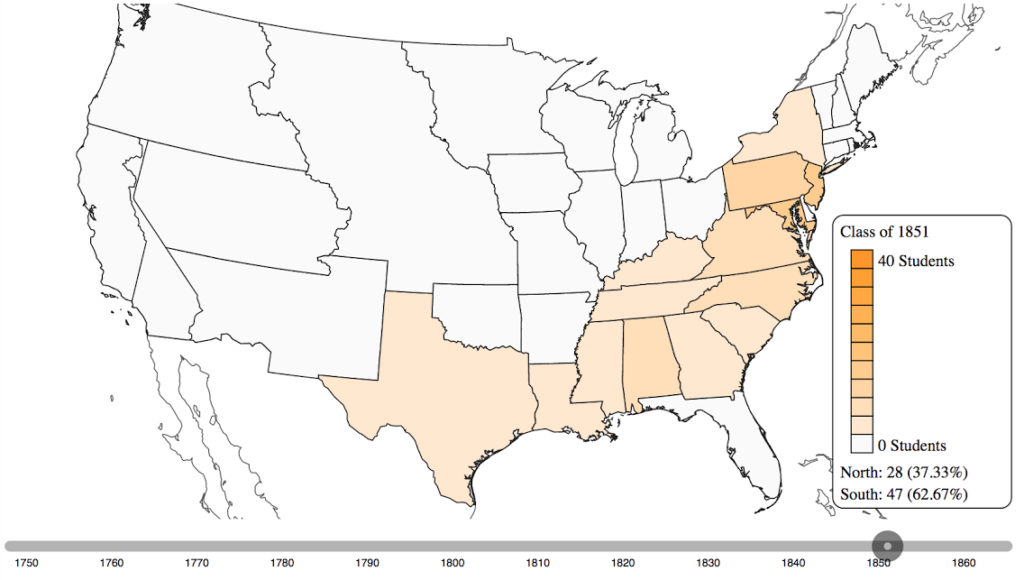

In November 2015, members of the Black Justice League occupied Nassau Hall to protest the legacy and persistence of racism on this campus. The night before the occupation, I met with one of the leaders, and we discussed the connection between our two projects. We discussed the university’s ostensible commitment to diversity and inclusion and how that commitment has come into conflict with historical patterns of exclusion and exploitation. The BJL’s activism opened the way for the Princeton & Slavery website, and their insights were critical for the project. Among other things, they suggested an emphasis on hard data and visuals, which led to our Student Origins Heat Map.

The map is based on the undergraduate alumni index compiled by the Princeton University Archives. It provides states of origin for over 6,500 students who attended the College of New Jersey between 1746 and 1865. The first thing you will notice is that there was a large population of students from southern slaveholding states. And the southern student population was unusually diverse. Altogether, during this period, about 2,400 residents of the slaveholding South attended the College, representing seventeen states and territories and at least 40% of all alumni. Our definition of “southern students” is open to debate. (Technically, New Jersey was a slave state until 1865.) But the overall pattern is clear. During the first half of the nineteenth century, only about 10% of the student body at Harvard and Yale came from the South. At Princeton, it was sometimes over 50%.

So, what explains this difference? The number of southern students at Princeton began to climb during the 1760s. This was part of a deliberate strategy pursed by President Witherspoon and his successors to recruit and enroll the sons of wealthy slaveholders. By the nineteenth century, Princeton had a firm reputation as a “southern college.” Edward Shippen (class of 1845) recalled a “preponderance of Southern students” on campus. In fact, between 1840 and 1860, eight graduating classes had more southern than northern students. The class of 1851 was about 63% southern, including representatives from Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. Over time, you can see how enrollment tracked the spread of the slave economy. As the institution became more powerful on the national level, slavery and racism became part of the DNA of Princeton.

The impact of southern students on campus was profound. Notorious for their bad behavior, they attacked and harassed abolitionists and precipitated riots in town. African Americans studying and working on campus were special targets. Southern students threw black workers out of windows, shot pistols at them, and otherwise harassed and demeaned them. At the same time, Princeton became renowned as a safe space for slaveholders. College affiliates actively opposed the abolitionist movement. Although critical of slavery, faculty members viewed abolition as a threat to the social and economic order. As Toni Morrison put it recently: “Slavery was always about money: free labor producing money for owners and industries.” Princeton’s faculty knew this, and they encouraged their students to put profits before people – property rights before human rights. The result was a catastrophic failure of moral leadership.

The impact of southern students on campus was profound. Notorious for their bad behavior, they attacked and harassed abolitionists and precipitated riots in town. African Americans studying and working on campus were special targets. Southern students threw black workers out of windows, shot pistols at them, and otherwise harassed and demeaned them. At the same time, Princeton became renowned as a safe space for slaveholders. College affiliates actively opposed the abolitionist movement. Although critical of slavery, faculty members viewed abolition as a threat to the social and economic order. As Toni Morrison put it recently: “Slavery was always about money: free labor producing money for owners and industries.” Princeton’s faculty knew this, and they encouraged their students to put profits before people – property rights before human rights. The result was a catastrophic failure of moral leadership.

Students’ impact after graduation, while difficult to measure, is worth further study. Many southern alumni went on to prominent careers in politics, government, and the law. In his authoritative history of Princeton, published for the school’s two-hundredth anniversary, Thomas Wertenbaker argues that the experience of living in New Jersey made southern students less partisan. The “southern boy” returning home, states Wertenbaker, lost his “old provincialism” and became “more cosmopolitan. Although still an ardent southerner, his sympathies were national rather than sectional.” Wertenbaker (a Virginian himself) offers no evidence to support this claim. In fact, the opposite seems at least as likely. Venturing North, in many cases for the first time, students from slaveholding families encountered challenges they would not have faced at home. Although New Jersey was a slave state, it had some abolitionists, and Princeton had a large and politically active free black population. Self-described “southern bloods” bonded together at the school, and their shared experiences gave them a common identity as southerners.

Consider Thomas Ancrum, a member of the class of 1838 from South Carolina. As a freshman, he helped to organize and lead a lynch mob. A group of about 60 students descended on Princeton’s black neighborhood, apprehended an abolitionist, burned his papers, and drove him out of town. The following year, Ancrum physically attacked black abolitionist Theodore Wright during the College commencement. The inaction of the college leadership, in both cases, underscored the school’s dual commitment to slavery and white supremacy. Ancrum left Princeton to manage his family’s plantation of over 200 slaves, and he worked as a recruiter for the Confederate Army. Consider Hilliard Judge (class of 1837). Like Ancrum, he helped to organize and lead the anti-abolition mob in town. Emboldened by his experience at Princeton, Judge moved to Alabama and became involved in proslavery politics. He wrote to Senator John C. Calhoun in 1849: “The public mind, is rapidly being prepared for what must come at last, the dissolution of the Union.”

Consider David Kaufman (class of 1833). Although born in Pennsylvania, Kaufman moved to Texas after graduation, where he became a senator and helped to usher Texas into the Union as a slave state. In 1850, he returned to Princeton to give the commencement address. In a rambling, hour-and-a-half-long screed, he compared abolitionism to atheism and communism and claimed that slavery was necessary for American freedom – a positive good for the country. Consider Jehu Orr (class of 1849), who became a founding member of the Confederate Congress. The list goes on. In fact, more Princeton graduates fought for the Confederacy than fought for the Union.

Consider Woodrow Wilson (class of 1879). While a sophomore, several of his fellow southerners launched a protest against a black seminary student who was auditing a class at the college. The student, a former slave, upset the racial hierarchy at Princeton. “If the intruder had busied himself with a broom or a feather-duster, they could doubtless have endured his presence,” reported the Princetonian, “but to see him taking notes ‘just like white folks’, was too much.” Wilson’s involvement in the incident is unclear. But he later wrote in his diary that blacks were “an ignorant and inferior race.” As one historian puts it, Princeton was “the first occasion that [Wilson] became really conscious of being a southerner.” When he graduated, he waxed poetic to a classmate from Georgia, about “our beloved South.” Of course, as president of Princeton and later the nation, Wilson promoted segregation and embraced white supremacy.

Consider Woodrow Wilson (class of 1879). While a sophomore, several of his fellow southerners launched a protest against a black seminary student who was auditing a class at the college. The student, a former slave, upset the racial hierarchy at Princeton. “If the intruder had busied himself with a broom or a feather-duster, they could doubtless have endured his presence,” reported the Princetonian, “but to see him taking notes ‘just like white folks’, was too much.” Wilson’s involvement in the incident is unclear. But he later wrote in his diary that blacks were “an ignorant and inferior race.” As one historian puts it, Princeton was “the first occasion that [Wilson] became really conscious of being a southerner.” When he graduated, he waxed poetic to a classmate from Georgia, about “our beloved South.” Of course, as president of Princeton and later the nation, Wilson promoted segregation and embraced white supremacy.

These are just some of the stories that emerge from the Princeton & Slavery website. The full student origins database is available online, so researchers and students can interact with this information and develop new interpretations and new insights. This is only the beginning. In my first meeting with the Black Justice League, and in subsequent conversations, they pointed out that the story of Princeton & Slavery is not over. What crimes are we complicit in today? What if we use our knowledge of history to direct our actions in a more ethical direction in the present? I hope our website will help to continue that conversation.