This year I was privileged to design and teach an experimental (and somewhat improvisational) course spanning multiple disciplines. It is one of a small number of Digital History courses offered at the undergraduate level in the United States and, to the best of my knowledge, the only course of its kind to require students to conceive, design, and execute an original historical website in a matter of weeks. Beginning with a short overview of the history of computing, the major part of the course deals with current debates and problems confronting historians in the Digital Age. Students read theoretical literature on topics such as the gender divide, big data, and the democratization of knowledge, as well as digital history projects spanning the range of human experience, from ancient Greece to modern Harlem. Guest speakers discussed the complexities of database design and the legal terrain of fair use, open access, and privacy. The complete syllabus is available here.

Unusually for a humanities class, the students engaged in a series of labs to build and test digital literacy skills. This culminated in a final project asking them to select, organize, and interpret a body of original source material. I solicited ideas and general areas of interest for the project and posted a list to the class blog that grew over the course of the semester. Students expressed interest in newspaper databases, amateur history and genealogy, text mining and topic modeling, local community initiatives, and communications, culture, and new media. I thought it was important to find a project that would speak to every student’s interest while not playing favorites with the subject matter. We considered a plan to scan and present an archive of old student and university publications. I thought it was a good idea. On the other hand, it would have involved at lot of time-consuming rote digitization, access to restricted library collections, and sharing of limited scanning facilities.

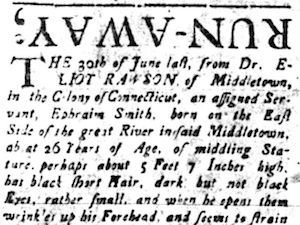

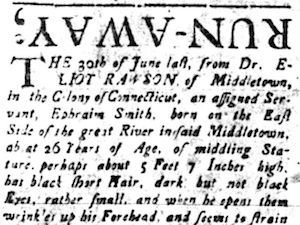

Ultimately, the students decided to build an interactive database of runaway advertisements printed in colonial and early national Connecticut. This seemed to satisfy every major area of interest on our list and, when I polled the class, there was broad consensus that it would be an interesting experiment. The project grew out of an earlier assignment, which asked students to review websites pertaining to the history of slavery and abolition. It also allowed me to draw on my academic background researching and teaching about runaways. We settled on Connecticut because it is a relatively small state with a small population, as well as home to the nation’s oldest continuously published newspaper. At the same time, it was an important colonial outpost and deeply involved in the slave trade and other forms of unfree labor on a variety of fronts.

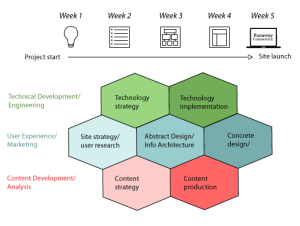

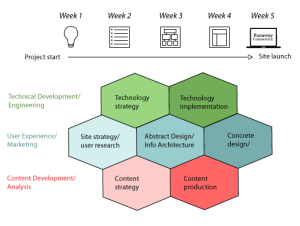

Drawing on the site reviews submitted earlier in the term, we brainstormed some ideas for what features would and would not work on our site. The students were huge fans of Historypin, universally acclaimed for both content and interface. So we quickly agreed that the site should have a strong geospatial component. We also agreed that the site should have a focus on accessibility for use in classrooms and by researchers as well as the general public. Reading about History Harvest, OutHistory.org, and other crowdsourced community heritage projects instilled a desire to reach out to and collaborate with local educators. Settling on a feasible research methodology was an ongoing process. Although initially focused on runaway slaves, I gently encouraged a broader context. Thus the final site presents ads for runaway children, servants, slaves, soldiers, wives, and prisoners and ties these previously disparate stories into a larger framework. Finally, a student who had some experience with web design helped us to map a work plan for the project based on the Web Style Guide by Patrick Lynch and Sarah Horton.

Drawing on the site reviews submitted earlier in the term, we brainstormed some ideas for what features would and would not work on our site. The students were huge fans of Historypin, universally acclaimed for both content and interface. So we quickly agreed that the site should have a strong geospatial component. We also agreed that the site should have a focus on accessibility for use in classrooms and by researchers as well as the general public. Reading about History Harvest, OutHistory.org, and other crowdsourced community heritage projects instilled a desire to reach out to and collaborate with local educators. Settling on a feasible research methodology was an ongoing process. Although initially focused on runaway slaves, I gently encouraged a broader context. Thus the final site presents ads for runaway children, servants, slaves, soldiers, wives, and prisoners and ties these previously disparate stories into a larger framework. Finally, a student who had some experience with web design helped us to map a work plan for the project based on the Web Style Guide by Patrick Lynch and Sarah Horton.

Since there were students from at least half a dozen different majors, with vastly different interests and skill sets, we needed a way to level the playing field, and specialized work groups seemed like a good way to do this. We sketched out the groups together in class and came up with four: Content, CMS, Outreach, and Accessibility. The Content Team researched the historiography on the topic and wrote most of the prose content, including the transcriptions of the advertisements. They used Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers database to mine for content and collated the resulting data using shared Google Docs. The CMS Team, composed mostly of computer science majors, focused on building the framework and visual feel for the site. Theoretically they could have chosen any content management system, although I pushed for Omeka and Neatline as probably the best platforms for what we needed to do. The Outreach Team created a twitter feed and a video documentary and solicited input about the site from a wide range of scholars and other professionals. The Accessibility Officer did extensive research and testing to make sure the site was fully compliant with open web standards and licenses.

The group structure had benefits and drawbacks. I tried to keep the system as flexible as possible. I insisted that major decisions be made by consensus and that group members post periodic updates to the class blog so that we could track our progress. Some students really liked it and floated around between different groups, helping out as necessary. I also received criticism on my evaluations from students who felt boxed in and complained that there was too much chaos and not enough communication between the groups. So I will probably rethink this approach in the future. One evaluator suggested that I ditch the collaborative project altogether and ask each student to create their own separate site, but that seems even more chaotic. In my experience, there are always students who want less group work and students who want more, and it is an ongoing struggle to find the right balance for a given class.

The assignment to design and publish an original historical site in a short amount of time, with no budget, almost no outside support, and only a general sense of what needs to be done is essentially a smaller, limited form of crowdsourcing. More accurately, it is a form of rapid development, in which the transition between design and production is extremely fast and highly mutable. Rapid development has been a mainstay of the technology industry for a while now. In my class, I cited the example of One Week | One Tool, in which a small group of really smart people get together and produce an original digital humanities tool. If they could do that over the course of a single week, I asked, what could an entire class of really smart people accomplish in a month?

The result, RunawayCT.org, is not anything fancy, but it is an interesting proof of concept. Because of the hit-or-miss nature of OCR on very old, poorly microfilmed newspapers, we could not get a scientific sample of advertisements. Figuring out how to properly select, categorize, format, and transcribe the data was no mean feat – although these are exactly the kinds of problems that scholarly history projects must confront on a daily basis. The Outreach Team communicated with the Readex Corporation throughout the project, and their representatives were impressively responsive and supportive of our use of their newspaper database. When the students asked Readex for access to their internal API so that we could automate our collection of advertisements, they politely declined. Eventually, I realized that there were literally thousands of ads, only a fraction of which are easily identified with search terms. So our selection of ads was impressionistic, with some emphasis on chronological breadth and on ads that were especially compelling to us.

Despite the students’ high level of interest in, even fascination with, the content of the ads, transcribing them could be tedious work. I attempted to apply OCR to the ad images using ABBYY FineReader and even digitized some newspaper microfilm reels to create high resolution copies, but the combination of eighteenth-century script and ancient, blurry microfilm rendered OCR essentially useless. Ads printed upside down, faded ink, and text disappearing into the gutters between pages were only a few of the problems with automatic recognition. At some point toward the end, I realized that my Mac has a pretty badass speech-to-text utility built into the OS. So I turned it on, selected the UK English vocabulary for the colonial period ads, and plugged in an old Rock Band mic (which doubles as an external USB microphone). Reading these ads, which are almost universally offensive, aloud in my room was a surreal experience. It was like reading out portions of Mein Kampf or Crania Americana, and it added a new materiality and gravity to the text. I briefly considered adding an audio component to the site, but after thinking about it for a while, in the cold light of day, I decided that it would be too creepy. One of my students pointed out that a popular educational site on runaway slaves is accompanied by the sounds of dogs barking and panicked splashing through rivers. And issues like these prompted discussion about what forms of public presentation would be appropriate for our project.

Despite the students’ high level of interest in, even fascination with, the content of the ads, transcribing them could be tedious work. I attempted to apply OCR to the ad images using ABBYY FineReader and even digitized some newspaper microfilm reels to create high resolution copies, but the combination of eighteenth-century script and ancient, blurry microfilm rendered OCR essentially useless. Ads printed upside down, faded ink, and text disappearing into the gutters between pages were only a few of the problems with automatic recognition. At some point toward the end, I realized that my Mac has a pretty badass speech-to-text utility built into the OS. So I turned it on, selected the UK English vocabulary for the colonial period ads, and plugged in an old Rock Band mic (which doubles as an external USB microphone). Reading these ads, which are almost universally offensive, aloud in my room was a surreal experience. It was like reading out portions of Mein Kampf or Crania Americana, and it added a new materiality and gravity to the text. I briefly considered adding an audio component to the site, but after thinking about it for a while, in the cold light of day, I decided that it would be too creepy. One of my students pointed out that a popular educational site on runaway slaves is accompanied by the sounds of dogs barking and panicked splashing through rivers. And issues like these prompted discussion about what forms of public presentation would be appropriate for our project.

I purposely absented myself from the site design because I wanted the students to direct the project and gain the experience for themselves. On the other hand, if I had inserted myself more aggressively, things might have moved along at a faster pace. Ideas such as building a comprehensive data set, or sophisticated topic modelling, or inviting the public to participate in transcribing and commenting upon the documents, had to be tabled for want of time. Although we collected some historical maps of Connecticut and used them to a limited extent, we did not have the opportunity to georeference and import them into Neatline. This was one of my highest hopes for the project, and I may still attempt to do it at some point in the future. I did return to the site recently to add a rudimentary timeline to our exhibit. Geocoding took only minutes using an API and some high school geometry, so I assumed the timeline would be just as quick. Boy, was I wrong. To accomplish what I needed, I had to learn some MySQL tricks and hack the underlying database. I also had to make significant alterations to our site theme to get everything to display correctly.

One of the biggest challenges we faced as a class was securing a viable workspace for the project. Technology Services wanted us to use their institutional Omeka site, with little or no ability to customize anything, and balked at the notion of giving students shell access to their own server space. Instead, they directed us to Amazon Web Services, which was a fine compromise, but caused delays getting our system in place and will create preservation issues in the future. As it is now, the site will expire in less than a year, and when I asked, there was little interest in continuing to pay for the domain. I was told saving the site would be contingent on whether or not it is used in other classes and whether it “receives decent traffic.” (Believe it or not, that’s a direct quote.) One wonders how much traffic most student projects receive and what relationship that should bear to their institutional support.

Although not a finely polished gem, RunawayCT.org demonstrates something of the potential of rapid development for digital history projects. As of right now, the site includes almost 600 unique ads covering over half a century of local history. At the very least, it has established a framework for future experimentation with runaway ads and other related content. Several of the students told me they were thrilled to submit a final project that would endure and be useful to the broader world, rather than a hastily-written term paper that will sit in a filing cabinet, read only by a censorious professor. Given all that we accomplished in such a short time span, I can only guess what could be done with a higher level of support, such as that provided by the NEH or similar institutions. My imagination is running away with the possibilities.

Cross-posted at HASTAC

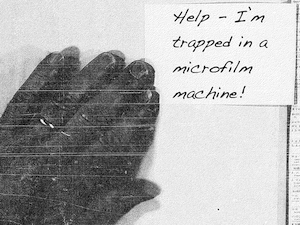

To me, it looks like a severed hand. All of us who use Google Books on a regular basis have seen them at some point, floating, disembodied, anonymous, usually feminine or non-white. People have been blogging about the hands for years. A Google worker famously lost his job after trying to film the bodies attached to them. The hands are printed in art books and compiled on Tumblr. Many of them evoke themes of race and class. Or, as the New Yorker put it, “a brown hand resting on a page of a beautiful old book.” The perceived disparity between the brown and the beautiful speaks volumes. Sometimes the hands communicate subtle messages. Consider the bejeweled hand pointing to a chapter in a biography of Napoleon. Or get lost in the psychedelic mystery that is A Serious Call to the Christian World, authored by “Jews.” One of my personal favorites is a small appendage with long nails and neon purple finger-condoms grasping the title page of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. Who says there is no poetry in the everyday? In an instant, “the invisible hand” of the market is laid bare. These glitches are the material traces of the workers who actually power the digital revolution. The severed hand is the embodiment of a history.

To me, it looks like a severed hand. All of us who use Google Books on a regular basis have seen them at some point, floating, disembodied, anonymous, usually feminine or non-white. People have been blogging about the hands for years. A Google worker famously lost his job after trying to film the bodies attached to them. The hands are printed in art books and compiled on Tumblr. Many of them evoke themes of race and class. Or, as the New Yorker put it, “a brown hand resting on a page of a beautiful old book.” The perceived disparity between the brown and the beautiful speaks volumes. Sometimes the hands communicate subtle messages. Consider the bejeweled hand pointing to a chapter in a biography of Napoleon. Or get lost in the psychedelic mystery that is A Serious Call to the Christian World, authored by “Jews.” One of my personal favorites is a small appendage with long nails and neon purple finger-condoms grasping the title page of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. Who says there is no poetry in the everyday? In an instant, “the invisible hand” of the market is laid bare. These glitches are the material traces of the workers who actually power the digital revolution. The severed hand is the embodiment of a history.